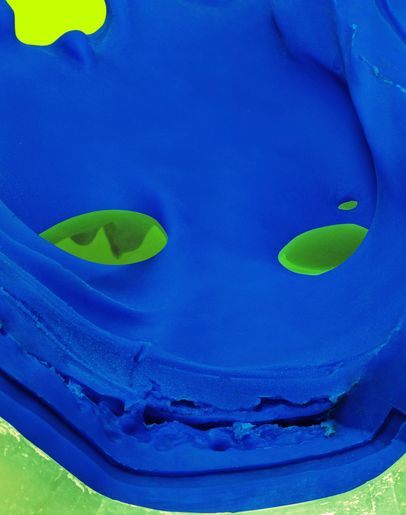

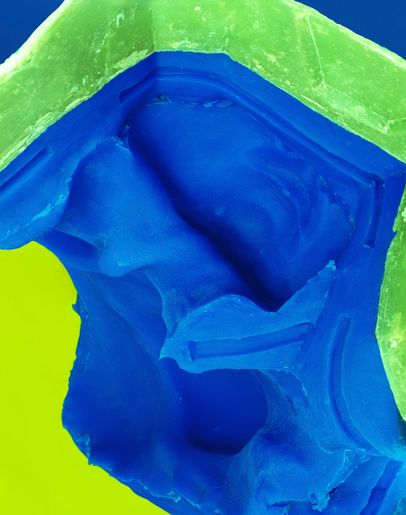

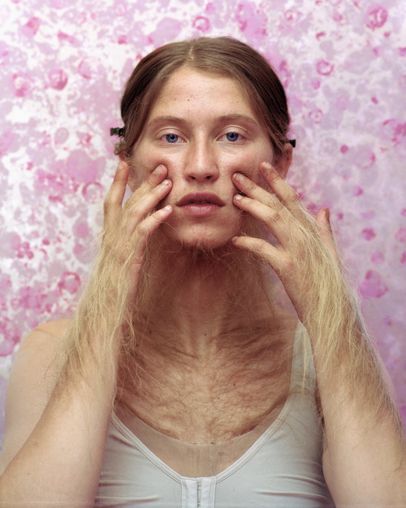

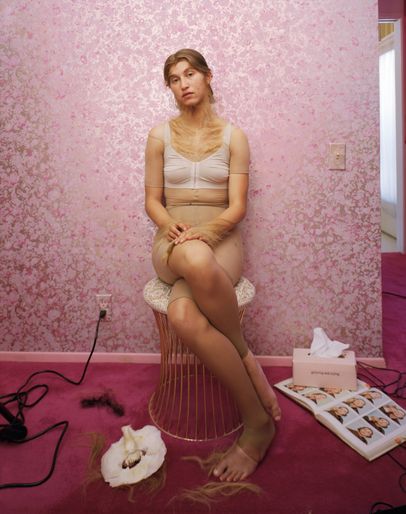

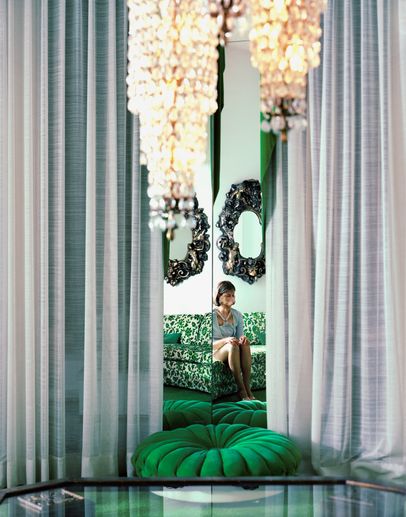

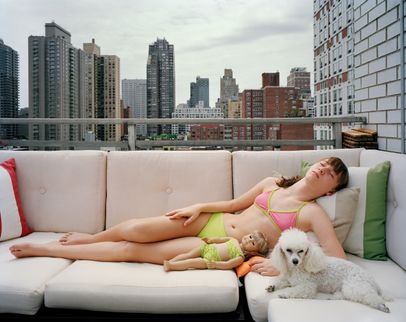

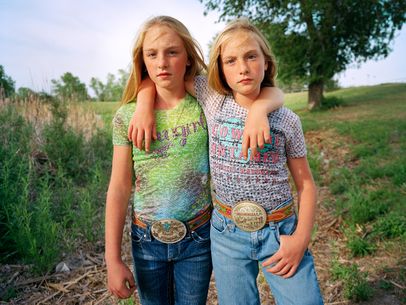

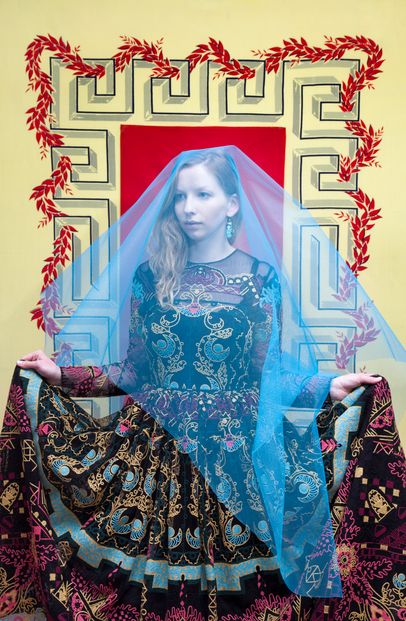

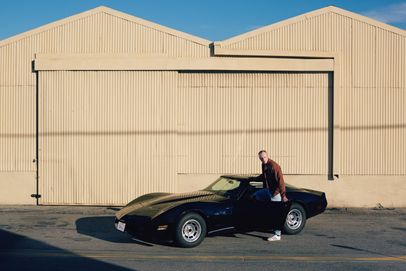

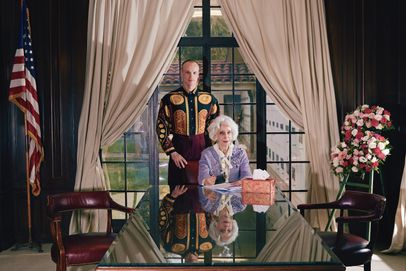

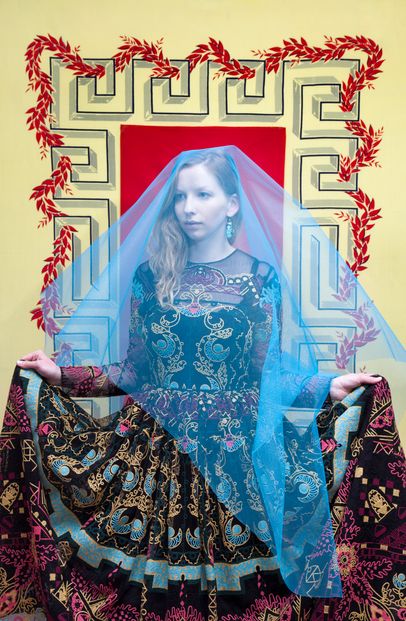

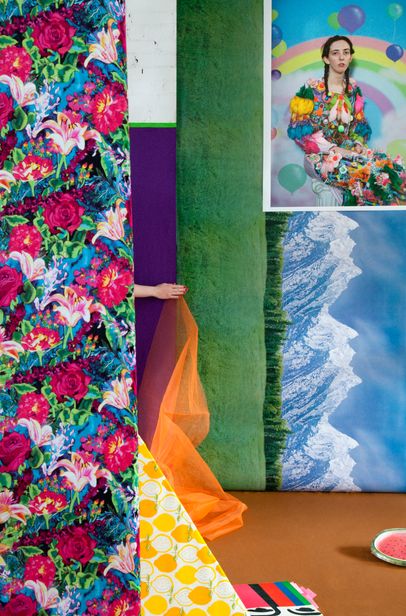

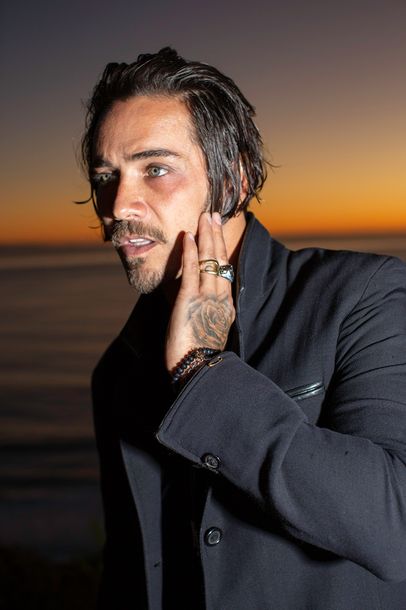

ILONA SZWARC I am girl and I want to be

Ilona Szwarc I am girl and I want to be

Ilona Szwarc I am girl and I want to be

Here's What Little Girls Are Made Of

Photographs by Ilona Szwarc

Words by Angella d'Avignon

IN 1991, THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF UNIVERSITY WOMEN published “Shortchanging Girls, Shortchanging America,” a national survey that assessed the self-esteem, educational experience, interest in math and science, and career aspirations of boys and girls aged 9 to 15. The organization’s findings established a strong link between the “sharp drop in self-esteem suffered by pre-adolescent and adolescent American girls to what they learn in the classroom” and determined that lower confidence in girls—what is known as “the confidence gap”—is not innate, but learned.

According to the survey, girls received significantly less attention than boys and were discouraged from pursuing math- and science-related degrees. (Girls of color were disproportionately affected.) "Construction of the glass ceiling begins not in the executive suite, but in the classroom," wrote Alice McKee, president of the AAUW Educational Foundation, in 1992. “By the time girls reach high school, they have been systematically tracked … away from areas of study that lead to high-paying jobs in science, technology, and engineering. America cannot afford to squander half its talent."

It seems that very little has changed since; girls continue to be discounted and undervalued. In 2015, psychologist Wiebke Bleidorn from the University of California, Davis, reported that the confidence gap not only continues well into adulthood, but is also culturally widespread. (The magnitude of the gap is larger in Western industrialized nations such as the United States, where capitalist economies and visions of achievement train girls and women to instinctively compare themselves to men as primary models of success.)

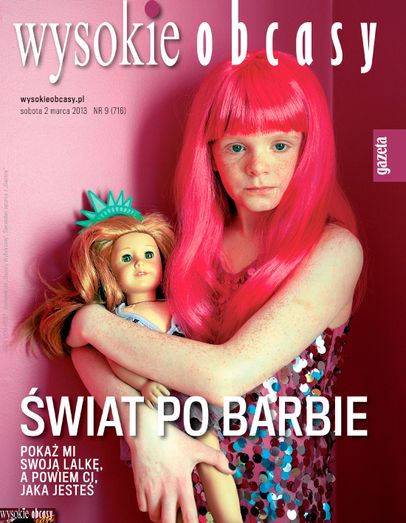

Studies show that middle school is the time when self esteem plummets the most. We interviewed six girls, ages 7 to 11, who not only envision their future successes with clarity, but are planning for it.

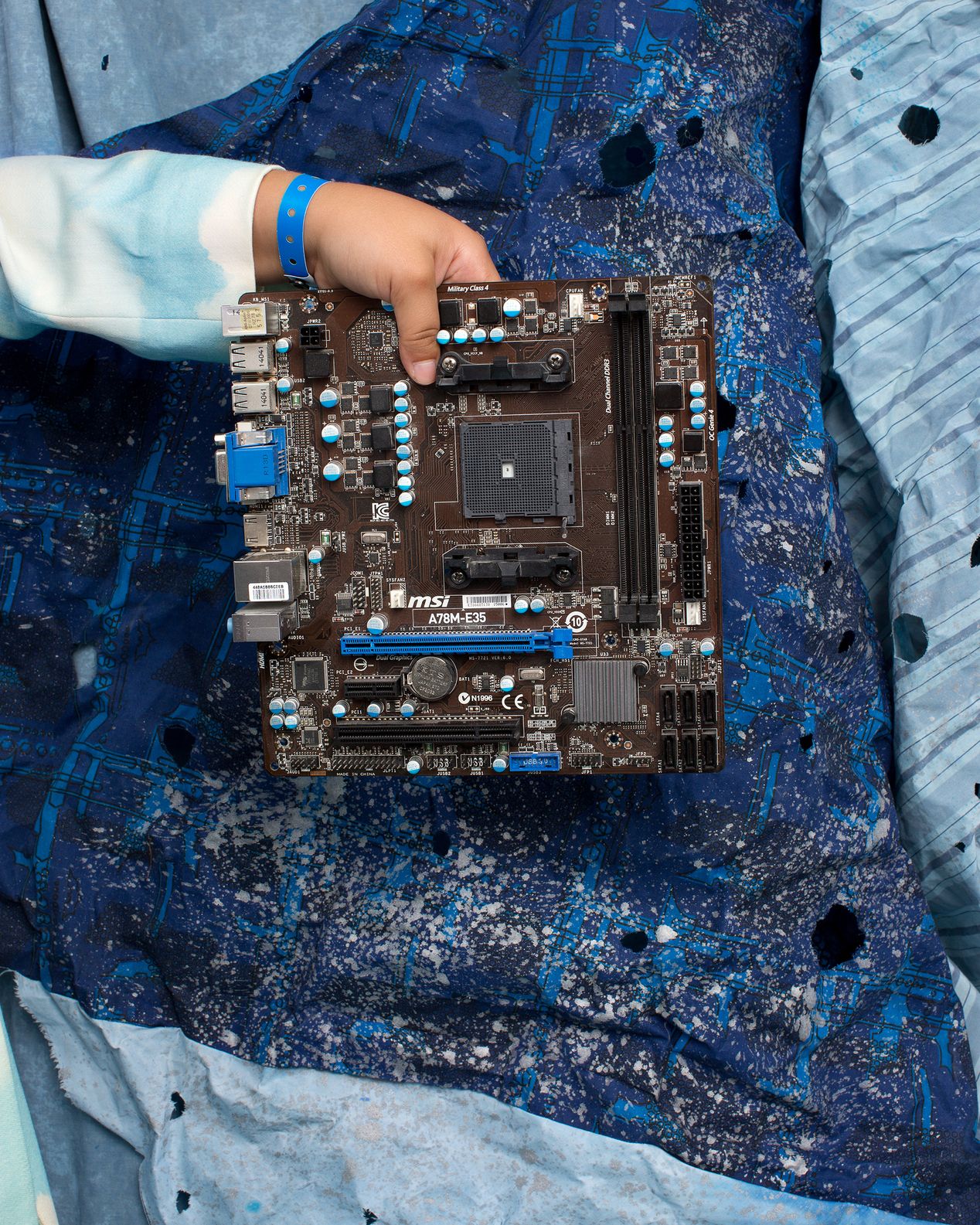

“As I have gotten older, my mom told me that I should probably be a scientist, so that I could invent the things I am interested in,” Zia says. “This last year, I started thinking that maybe I shouldn’t be an inventor or scientist, because boys always say that girls can’t do that. But I know they are wrong.”

According to the most recent census data, women comprise 46.8 percent of the U.S. workforce, but only 29 percent of those women work in STEM or STEM-related fields. In 2016, 49 percent of science-related degrees went to women, but over 50 percent will eventually leave the field. As of 2016, only 14 percent of the engineering workforce is female. And higher education doesn’t close the wage gap, either: on average, women with more advanced degrees earn proportionally less than their male equivalents, as compared to women and men who have spent less time in school.

“If life doesn’t go my way, I always have a backup plan,” says Darielle. “I’m determined and ready for whatever comes my way. Always confident.”

As Pointe magazine reports, ballet has a significant diversity problem, with usually only two to three dancers of color per company.

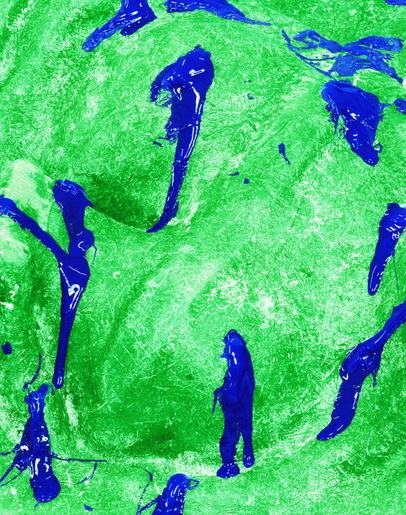

Ashlyn describes her future vividly and says, as a gemologist, that she wants to “explore caves and find gems and diamonds.” Her imagination is expansive. **“**I like to color in blank pictures, then I color in whatever color I want.”

Though women’s presence in the field of archaeology has dramatically increased since 1997, it’s still male-dominated. But if that keeps changing at the current rate—65 percent of archaeologists aged 20 to 29 are women—the scales could tip, making archaeology a significantly female-led field in the next 10 to 15 years. (Note that these numbers are from the U.K., not the U.S.)

“I kept asking my mom if I could help homeless people when I grow up. It’s a very important job,” says Jazmine. “I am strong. I don’t bully. And I like to help.”

Though women continue to be paid an average of 80 cents for every dollar made by a man, women in the top 25 percent donate 156 percent more money than do men in the same income bracket. According to the Women’s Philanthropy Institute at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, women at all income levels still give more than men, even though women make less and live longer.

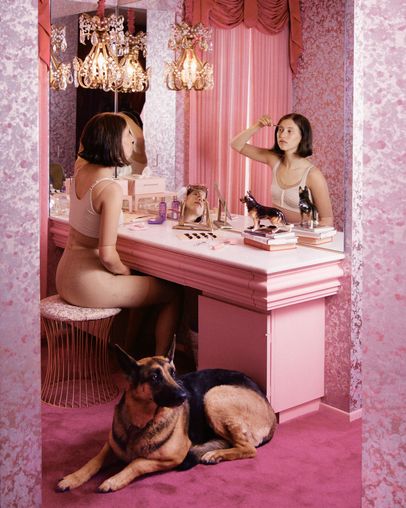

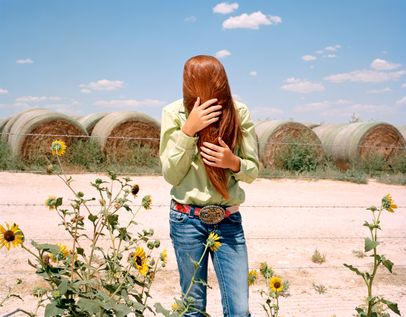

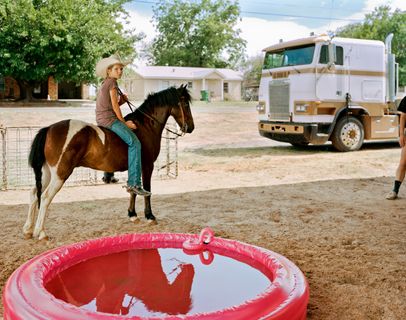

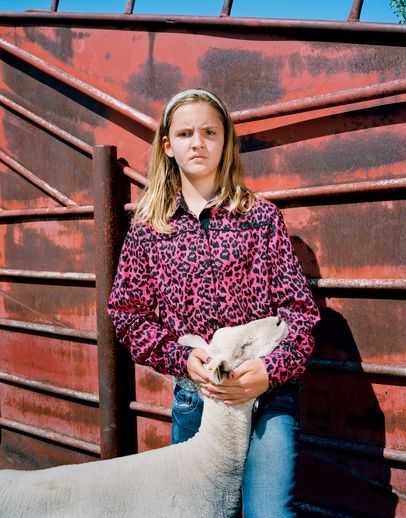

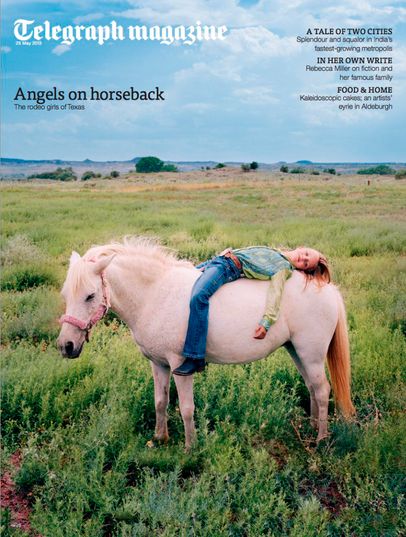

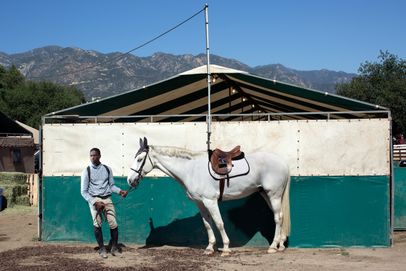

“Horseback riding is like a language. If you forget it, it takes a lot of time to remember it,” says Asia. The key, she says, is to stay present. “Be in yourself at moments, and let your imagination flow sometimes.”

In the equestrian world, where competition is coed, roughly 75 percent of competitors in North America and Europe are female. But in many events, the majority of the people who end up on the podium at competitions such as the Olympics are still male. Many argue that this approach conceals sexist decision-making by panels of judges and Olympic committees which are made up of mostly, if not entirely, men.

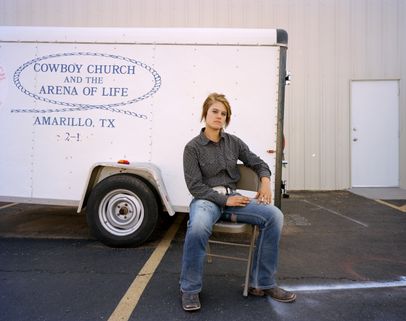

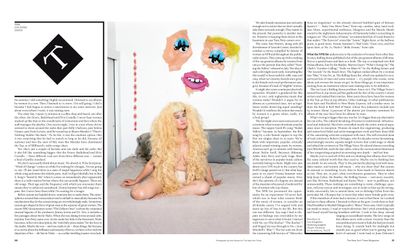

Adora says her humor can be ribald. (“I still enjoy potty humor.”) When asked who some of her heroes are, Adora is straightforward and unapologetic. “I am my own favorite comedian,” she says.

Despite the rise in visibility for female comics, the gender gap in the comedy world persists: in 2013, the ten highest-paid comedians were male. Hopefully, the situation is in the midst of a shift, as the proportion of Comedy Central specials fronted by a woman rose from 8 percent in 2012, to 29 percent in 2016.